Black Socialites: Then, Now, and Still Becoming

How sustainable is your reputation? How durable is your social status when the room changes, when the platform disappears, when the applause quiets? Can you move a room, or does your influence hinge on how you appear inside one or two‑letter apps?

These are not moral questions. They are structural ones.

We are living in a moment saturated with calls to action. Everyone is being asked to use their influence, people of color and those who are not, because our current way of life, culturally and economically, is proving itself unsustainable. And yet, the loudest forms of influence often feel the most fragile.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about reputation not as visibility, but as infrastructure.

Influence, Measured

Last year’s Met Gala offered a monumental financial display of Black and brown presence. The 2025 gala, centered on so‑called Black dandyism, reportedly generated over $31 million in a single night for the Costume Institute. One evening. One staircase. One spectacle.

Contrast that with the Ebony Fashion Fair, founded by Eunice W. Johnson. For more than 50 years (1958 - 2009), the Fair traveled city to city, bringing couture into Black communities that were otherwise excluded from it. Over its lifetime, it raised more than $55 million, not for fashion itself, but for scholarships, hospitals, and community institutions. The money circulated. The access multiplied. The impact endured.

This comparison is not about competition. It’s about sustainability.

What lasts longer: a night of cultural attention, or decades of intentional circulation?

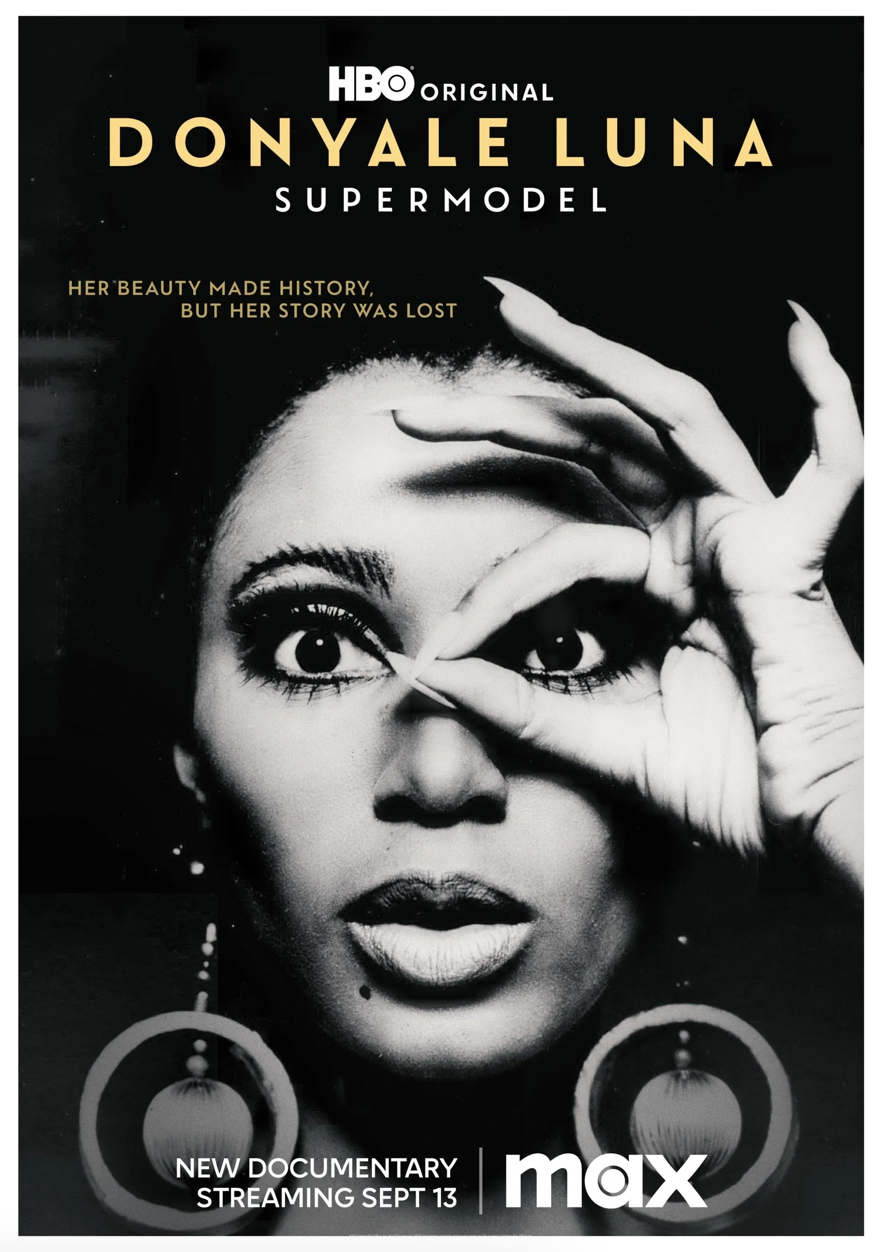

Donyale Luna and the Cost of Proximity

Around the same time, I revisited the life of Donyale Luna, the first Black model to appear on the cover of British Vogue in 1966, often cited as fashion’s first Black supermodel. Luna was visionary, ethereal, and deeply isolated. She was also frequently criticized for her perceived distance from the Civil Rights Movement and for her complicated relationship to her own Blackness.

Her story is often flattened into accusation or tragedy, but it reveals something more uncomfortable: proximity without power is still precarity. Representation without community is exposure.

The irony remains that many still believe Beverly Johnson was the first Black woman to cover Vogue, when in fact she was the first to do so for American Vogue in 1974. History compresses nuance when it becomes inconvenient.

The Socialite, Reconsidered

Which brings me back to the socialite.

Before influencer was a job title, there were Black socialites.

They were not defined by follower counts or brand deals. They were defined by access, taste, connection, and responsibility to community. Black socialites moved through rooms with intention, not to be seen, but to circulate.

They were connectors. Cultural translators. Patrons of art, fashion, music, and ideas.

They understood that proximity is power, and that power is best used to open doors, not guard them.

They fundraised quietly. Advocated strategically. Hosted with purpose.

Their influence lived in group chats, not public callouts. In shared meals, shared travel, shared memory. Community was maintained, not performed.

What did they wear?

Not trends, intention.

Dress functioned as language: situational, thoughtful, deeply contextual. Black socialites understood that style was never separate from politics, history, or consequence.

Celebrity vs. Circulation

We often confuse celebrity with social power.

Diahann Carroll and Jane Fonda were both globally famous actresses, but at their core, they operated as socialites. They used visibility as leverage, not currency. They connected people who needed one another. They opened rooms. They stayed long enough to make change possible.

The question isn’t intention. It’s outcome.

Does the influence circulate beyond the moment? Does it create pathways for others when the lights go down?

Sustainability, Revisited

Social media has turned influence into spectacle, for everyone. But the consequences of that shift land differently on Black socialites, whose historical role has always been relational rather than performative.

Sustainable reputation is not built on constant visibility. It’s built on trust, continuity, and the quiet maintenance of community.

It knows when to be visible, and when to be strategic.

It invests in experiences, not just objects.

It builds a life that allows freedom: culturally, intellectually, socially.

Black socialites are not nostalgic figures.

They are contemporary architects.

And they are still becoming.

(Image: Donyale Luna 2023 HBO Documentary Cover Art)